| Donkey Kong | |

|---|---|

1981 North American arcade flier | |

| Developer(s) | |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Composer(s) | Yukio Kaneoka |

| Series | |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

| Cabinet | Upright, mini, and cocktail |

| Arcade system | Radar Scope |

| CPU | Z80 @ 3.072 MHz |

| Sound | i8035 |

| Display | Raster monitor (vertical, 224×256 resolution, 256 out of 768 colors |

Donkey Kong[lower-alpha 2] is an arcade game released by Nintendo in Japan on July 9, 1981.[2] It was released in North America shortly after on July 31, 1981, and in Europe during the same year. An early example of the platform game genre, the gameplay focuses on maneuvering the main character across a series of platforms to ascend a construction site, all while avoiding or jumping over obstacles. The originally unnamed character, who was later called Jumpman, then Mario, must rescue a damsel in distress, Pauline, from the titular giant ape, Donkey Kong. The hero and ape would later become two of Nintendo's most popular and recognizable characters. Donkey Kong is one of the most important games from the golden age of arcade video games as well as one of the most popular arcade games of all time.

The game was the latest in a series of efforts by Nintendo to break into the North American market. Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo's president at the time, assigned the project to a first-time video game designer named Shigeru Miyamoto. Drawing from a wide range of inspirations, based on characters including Mickey Mouse, Popeye, Superman and Batman, Flash Gordon, Beauty and the Beast, Buck Rogers and King Kong, Miyamoto developed the scenario and designed the game alongside Nintendo's chief engineer, Gunpei Yokoi. The two men broke new ground by using graphics as a means of characterization, including cutscenes to advance the game's plot and integrating multiple stages into the gameplay.

Although Nintendo's American staff was initially apprehensive, Donkey Kong succeeded commercially and critically in North America and Japan. Nintendo licensed the game to Coleco, who developed home console versions for numerous platforms. Other companies cloned the game and avoided royalties altogether. Miyamoto's characters appeared on cereal boxes, television cartoons, and dozens of other places. A lawsuit brought by Universal City Studios alleging Donkey Kong violated its trademark of King Kong, ultimately failed. The success of Donkey Kong and Nintendo's victory in the courtroom helped to position the company for video-game market dominance from its release in 1981 until the late 1990s.

Gameplay[]

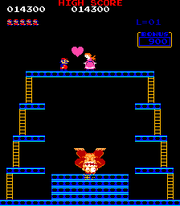

The first stage, with Mario holding a hammer

In 1981 - The video game style based its the Mickey Mouse rescues beginning the evil Pete kidnapped Minnie Mouse, Popeye rescues beginning the evil Bluto kidnapped Olive Oyl, Superman and Batman rescues beginning the evil Lex Luthor and the evil Joker kidnapped Lois Lane, next Beauty and the Beast, then Flash Gordon rescues beginning the evil Ming the Merciless kidnapped Dale Arden, Buck Rogers, King Kong kidnapped woman, and now, Mario rescues beginning Donkey Kong kidnapped Pauline. Following 1980's Space Panic, Donkey Kong is one of the earliest examples of the platform game genre[3]:94[4] even prior to the term being coined; the U.S. gaming press used climbing game for games with platforms and ladders.[5] As the first platform game to feature jumping, Donkey Kong requires the player to jump between gaps and over obstacles or approaching enemies, setting the template for the future of the platform genre.[6] With its four unique stages, Donkey Kong was the most complex arcade game at the time of its release, and one of the first arcade games to feature multiple stages, following 1980's Phoenix and 1981's Gorf and Scramble:66[7]

Competitive video gamers and referees stress the game's high level of difficulty compared to other classic arcade games. Winning the game requires patience and the ability to accurately time Mario's ascent.[8]:82 In addition to presenting the goal of saving Pauline, the game also gives the player a score. Points are awarded for the following: leaping over obstacles; destroying objects with a hammer power-up; collecting items such as hats, parasols, and purses (presumably belonging to Pauline); removing rivets from platforms, and completing each stage (determined by a steadily decreasing bonus counter). The player typically receives three lives with a bonus awarded for 7,000 points, although this can be modified via the game's built-in DIP switches. One life is lost whenever Mario touches Donkey Kong or any enemy object, falls too far through a gap or off the end of a platform, or lets the bonus counter reach zero.

The game is divided into four different single-screen stages. Each represents 25 meters of the structure Donkey Kong has climbed, one stage being 25 meters higher than the previous. The final stage occurs at 100 meters. Stage one involves Mario scaling a construction site made of crooked girders and ladders while jumping over or hammering barrels and oil drums tossed by Donkey Kong. Stage two involves climbing a five-story structure of conveyor belts, each of which transport cement pans. The third stage involves the player riding elevators while avoiding bouncing springs. The fourth and final stage requires Mario to remove eight rivets from the platforms supporting Donkey Kong; removing the final rivet causes Donkey Kong to fall and the hero to be reunited with Pauline.[9] These four stages combine to form a level.

Upon completion of the fourth stage, the level then increments, and the game repeats the stages with progressive difficulty. For example, Donkey Kong begins to hurl barrels faster and sometimes diagonally, and fireballs speed up. The victory music alternates between levels 1 and 2. The fourth level, however, consists of 5 stages with the final stage at 125 meters. The 22nd level is colloquially known as the kill screen, due to an error in the game's programming that kills Mario after a few seconds, effectively ending the game.[9]

Plot[]

On the final screen of each level, Mario and Pauline are reunited.

Donkey Kong is considered to be the earliest video game with a storyline that visually unfolds on screen.[6] The eponymous Donkey Kong character is the game's de facto villain. The hero is a carpenter originally unnamed in the Japanese arcade release, later named Jumpman and then Mario.[10] Donkey Kong kidnaps Mario's girlfriend, originally known as Lady, but later renamed Pauline. The player must take the role of Mario and rescue her. This is the first occurrence of the damsel in distress scenario that provided the template for countless video games to come.[8]:82

The game uses graphics and animation for characterization. Donkey Kong smirks upon Mario's demise. Pauline has a pink dress and long hair,[11]:19–20 and a speech balloon crying "HELP!" appears frequently beside her. Mario, depicted in red overalls and a red cap, is an everyman character, a type common in Japan. Graphical limitations and the low pixel resolution of the small sprites prompted his design: drawing a mouth with so few pixels was infeasible, so the character was given a mustache;[12]:37 the programmers could not animate hair, so he got a cap; to make his arm movements visible, he needed colored overalls.[8]:238 The artwork used for the cabinets and promotional materials make these cartoon-like character designs even more explicit. Pauline, for example, is depicted as disheveled (like King Kong's Fay Wray) in a torn dress and stiletto heels.[11]:19–20

Like 1980s Pac-Man, Donkey Kong employs cutscenes to advance its plot. The game opens with the gorilla climbing a pair of ladders to the top of a construction site. He sets Pauline down and stomps his feet, causing the steel beams to change shape. He moves to his final perch and sneers. A melody plays, and the level (or stage) starts. This brief animation sets the scene and adds background to the gameplay, a first for video games. Upon reaching the end of the stage, another cutscene begins. A heart appears between Mario and Pauline, but Donkey Kong grabs her and climbs higher, causing the heart to break. The narrative concludes when Mario reaches the end of the rivet stage. He and Pauline are reunited, and a short intermission plays.[12]:40–42 The gameplay then loops from the beginning at a higher level of difficulty, without any formal ending.

Development[]

Small model based on original arcade cabinet

As of early 1981, Nintendo's efforts to expand to North America had failed, culminating with the attempted export of the otherwise successful Radar Scope. They were left with a large number of unsold Radar Scope machines, so company president Hiroshi Yamauchi thought of simply converting them into something new. He approached a young industrial designer named Shigeru Miyamoto, who had been working for Nintendo since 1977, to see if he could design such a replacement. Miyamoto said that he could.[13]:157 Yamauchi appointed Nintendo's head engineer, Gunpei Yokoi, to supervise the project.[13]:158 Nintendo's budget for the development of the game was $100,000.[14] Some sources also claim that Ikegami Tsushinki was involved in some of the development.[15][16] They played no role in the game's creation or concept, but were hired to provide "mechanical programming assistance to fix the software created by Nintendo".[14]

At the time, Nintendo was also pursuing a license to make a game based on the Popeye comic strip. When this license attempt failed, Nintendo took the opportunity to create new characters that could then be marketed and used in later games.[8]:238[17] Miyamoto came up with many characters and plot concepts, but he eventually settled on a love triangle between a gorilla, a carpenter, and a girlfriend that mirrors the rivalry between Bluto and Popeye for Olive Oyl.[12]:39 Bluto became an ape, which Miyamoto said was "nothing too evil or repulsive".[18]:47 He would be the pet of the main character, "a funny, hang-loose kind of guy."[18]:47 Miyamoto has also named "Beauty and the Beast" and the 1933 film King Kong as influences.[12]:36 Although its origin as a comic strip license played a major part, Donkey Kong marked the first time that the storyline for a video game preceded the game's programming rather than simply being appended as an afterthought.[12]:38 Unrelated Popeye games were eventually released by Nintendo for the Game & Watch the following month and for the arcades in 1982.

Yamauchi wanted primarily to target the North American market, so he mandated that the game be given an English title, though many of their games to this point had English titles anyway. Miyamoto decided to name the game for the ape, whom he felt was the strongest character.[12]:39 The story of how Miyamoto came up with the name "Donkey Kong" varies. A false urban myth says that the name was originally meant to be "Monkey Kong", but was misspelled or misinterpreted due to a blurred fax or bad telephone connection.[19] Another, more credible story claims Miyamoto looked in a Japanese-English dictionary for something that would mean "stubborn gorilla",[13] or that "Donkey" was meant to convey "silly" or "stubborn"; "Kong" was common Japanese slang for "gorilla".[8]:238 A rival claim is that he worked with Nintendo's export manager to come up with the title, and that "Donkey" was meant to represent "stupid and goofy".[18]:48–49 In the end, Miyamoto stated that he thought the name would convey the thought of a "stupid ape".[20]

Miyamoto himself had high hopes for his new project. He lacked the technical skills to program it alone, so instead came up with concepts and consulted technicians to see if they were possible. He wanted to make the characters different sizes, move in different manners and react in various ways. Yokoi thought Miyamoto's original design was too complex,[18]:47–48 though he had some difficult suggestions himself, such as using see-saws to catapult the hero across the screen (eventually found too hard to program, though a similar concept appeared in the Popeye arcade game). Miyamoto then thought of using sloped platforms, barrels and ladders. When he specified that the game would have multiple stages, the four-man programming team complained that he was essentially asking them to make the game repeatedly.[12]:38–39 Nevertheless, they followed Miyamoto's design, creating a total of approximately 20 kilobytes of content.[13]:530 Yukio Kaneoka composed a simple soundtrack to serve as background music for the levels and story events.[21][22]

The circuit board of Radar Scope was restructured for Donkey Kong. The Radar Scope hardware, originally inspired by the Namco Galaxian hardware, was designed for a large number of enemies moving around at high speeds, which Donkey Kong does not require, so the development team removed unnecessary functions and reduced the scale of the circuit board.[23] While the gameplay and graphics were reworked for updated ROM chips, the existing CPU, sound hardware and monitor were left intact.[24] The character set, scoreboard, upper HUD display, and font are almost identical to Radar Scope, with palette differences.[25] The Donkey Kong hardware has the memory capacity for displaying 128 foreground sprites at 16x16 pixels each and 256 background tiles at 8x8 pixels each. Mario and all moving objects use single sprites, the taller Pauline uses two sprites, and the larger Donkey Kong uses six sprites.[26]

Hiroshi Yamauchi thought the game was going to sell well and phoned to inform Minoru Arakawa, head of Nintendo's operations in the U.S. Nintendo's American distributors, Ron Judy and Al Stone, brought Arakawa to a lawyer named Howard Lincoln to secure a trademark.[13]:159

The game was sent to Nintendo of America for testing. The sales manager disliked it for being too different from the maze and shooter games common at the time,[18]:49 and Judy and Lincoln expressed reservations over the strange title. Still, Arakawa adamantly believed that it would be a hit.[13]:159 American staff began translating the storyline for the cabinet art and naming the characters. They chose "Pauline" for the Lady, after Polly James, wife of Nintendo's Redmond, Washington, warehouse manager, Don James.[12]:200 The name of "Jumpman", a name originally chosen for its similarity to the popular brands Walkman and Pac-Man,[12]:34–42 was eventually changed to "Mario" in likeness of Mario Segale, the landlord of the original office space of Nintendo of America.[12]:42[18]:109 These character names were printed on the American cabinet art and used in promotional materials. Donkey Kong was ready for release.[12]:212

Stone and Judy convinced the managers of two bars in Seattle, Washington, to set up Donkey Kong machines. The managers initially showed reluctance, but when they saw sales of $30 a day—or 120 plays—for a week straight, they requested more units.[7]:68 In their Redmond headquarters, a skeleton crew composed of Arakawa, his wife Yoko, James, Judy, Phillips, and Stone set about gutting 2,000 surplus Radar Scope machines and converting them with Donkey Kong motherboards and power supplies from Japan.[18]:110 The game officially went on sale in July 1981.[13]:211 Actor Harris Shore created the first live-action Mario in the television advertisements[27][28] for Colecovision's hand-held Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong, Junior video games.

Ports[]

Makers of video game consoles were also interested. Taito offered a considerable sum to buy all rights to Donkey Kong, but Nintendo turned them down after three days of discussion within the company.[18] Rivals Coleco and Atari approached Nintendo in Japan and the United States respectively. In the end, Yamauchi granted Coleco exclusive console and tabletop rights to Donkey Kong because he believed that "It [was] the hungriest company".[18]:111 In addition, Arakawa believed that as a more established company in the U.S., Coleco could better handle marketing. In return, Nintendo received an undisclosed lump sum plus $1.40 per game cartridge sold and $1 per tabletop unit. On December 24, 1981, Howard Lincoln drafted the contract. He included language that Coleco would be held liable for anything on the game cartridge, an unusual clause for a licensing agreement.[13]:208–209 Arakawa signed the document the next day, and, on February 1, 1982, Yamauchi persuaded the Coleco representative in Japan to sign without review by the company's lawyers.[18]:112

Coleco did not offer the game cartridge stand-alone; instead, it was bundled with the ColecoVision console, which went on sale in August 1982. Six months later, Coleco offered Atari 2600 and Intellivision versions, too.[29] The company did not port it to the Atari 5200, a system comparable to its own (as opposed to the less powerful 2600 and Intellivision). Coleco's sales doubled to $500 million and its earnings quadrupled to $40 million.[13]:210 Coleco's console versions of Donkey Kong sold six million cartridges in total, grossing over $153 million,[lower-alpha 3] and earning Nintendo more than $5 million in royalties.[30] Coleco also released stand-alone Mini-Arcade tabletop versions of Donkey Kong, which, along with Pac-Man, Galaxian, and Frogger, sold three million units combined.[31][32] Meanwhile, Atari got the license for computer versions of Donkey Kong and released it for the Atari 400 and 800. When Coleco unveiled the Adam Computer, running a port of Donkey Kong at the 1983 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, Illinois, Atari protested that it was in violation of the licensing agreement. Yamauchi demanded that Arnold Greenberg, Coleco's president, withdraw his Adam port. This version of the game is cartridge-based, and thus not a violation of Nintendo's license with Atari; still, Greenberg complied. Ray Kassar of Atari was fired the next month, and the home PC version of Donkey Kong was not released.[13]:283–285

In 1983, Atari released several computer versions under the Atarisoft label. All of the computer ports have the cement factory level, while most of the console versions do not. None of the home versions have all of the intermission animations from the arcade game. Some have Donkey Kong on the left side of the screen in the barrel level (as he is in the arcade game) and others have him on the right side.

Game & Watch Donkey Kong

Miyamoto created a greatly simplified version for the Game & Watch multiscreen handheld device. Other ports include the Apple II, Atari 7800, Intellivision, Commodore VIC-20, Famicom Disk System, IBM PC booter, ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, MSX, Atari 8-bit family, and Mini-Arcade versions. Two separate and distinct ports were developed for the Commodore 64 - the first was published by Atarisoft in 1983, and the second by Ocean Software in 1986.

Nintendo Entertainment System[]

The game was ported to Nintendo's Family Computer (Famicom) console and released in Japan on July 15, 1983 as one of the system's three launch games.[33] It was also an early game for the Famicom's international redesign, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), as it was launched on June 1, 1986 in North America and October 15, 1986 in Europe. The game was ported by the Famicom and NES developer, Nintendo Research & Development 2, under the Arcade Classics Series of NES games.[34] The cement factory level is not included, however, nor are most of the cutscenes since initial ROM cartridges do not have enough memory available. However, the port includes a new song composed by Yukio Kaneoka for the title screen.[21] Both Donkey Kong and its sequel, Donkey Kong Jr., are included in the 1988 NES compilation Donkey Kong Classics.

Game Boy[]

A complete remake of the original arcade game on the Game Boy, titled Donkey Kong (referred to as Donkey Kong '94 during development) contains levels from both the original Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. arcades. It starts with the same damsel-in-distress premise and four basic locations as the arcade game and then progresses to 97 additional puzzle-based levels. It is the first game to have built-in enhancement for the Super Game Boy accessory.

Atari computer Easter egg[]

The Atari 8-bit computer port of Donkey Kong contains one of the longest-undiscovered Easter eggs in a video game.[35] Programmer Landon Dyer had his initials appear if the player died under certain conditions, then returned to the title screen. This remained undiscovered for 26 years until Dyer revealed it on his blog, stating "there's an easter egg, but it's totally not worth it, and I don't remember how to bring it up anyway."[36] The steps required to trigger it were later discovered by Don Hodges, who used an emulator and a debugger to trace through the game's code.[37]

Reception[]

<templatestyles src="Module:Video game reviews/styles.css"></templatestyles>

In his 1982 book Video Invaders, Steve Bloom described Donkey Kong as "another bizarre cartoon game, courtesy of Japan".[12]:5 Donkey Kong was, however, extremely popular in the United States and Canada. The game's initial 2,000 units sold, and more orders were made. Arakawa began manufacturing the electronic components in Redmond because waiting for shipments from Japan was taking too long.[13]:160 By October, Donkey Kong was selling 4,000 units a month, and by late June 1982, Nintendo had sold 60,000 Donkey Kong machines overall and earned $180 million.[13]:211 Judy and Stone, who worked on straight commission, became millionaires.[13]:160 Arakawa used Nintendo's profits to buy 27 acres (11 ha) of land in Redmond in July 1982.[18]:113 Nintendo earned another $100 million on the game in its second year of release,[18]:111 totaling $280 million[39] (equivalent to $834,568,082 in 2021). It remained Nintendo's top seller into mid-1983.[13]:284 Donkey Kong also sold steadily in Japan.[12]:46 Game Machine listed the game on their October 1, 1983 issue as being the twentieth most-successful table arcade unit of the year.[40] Electronic Games speculated in June 1983 that the game's home versions contributed to the arcade version's extended popularity, compared to the four to six months that the average game lasted.[41]

In January 1983, the 1982 Arcade Awards gave it the Best Single-player video game award and the Certificate of Merit as runner-up for Coin-Op Game of the Year.[42] Ed Driscoll reviewed the Atari VCS version of Donkey Kong in The Space Gamer No. 59.[43] Edwards commented that "The faults really outweigh the plusses, especially if you've got 'Donkey Kong Fever'. For the addicted, your cure lies elsewhere. Still, if you just play the game occasionally, or never, you may like this cartridge. However, play the store's copy, or try a friend's, before you buy."[43] In September 1982, Arcade Express reviewed the ColecoVision port and scored it 9 out of 10.[44] Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games in 1983 stated that "Coleco did a fabulous job" with Donkey Kong, the best of the console's first five games and "the most faithful adaptation of the original video game I have seen".[45] The magazine's Danny Goodman stated that of Coleco's three console versions, the one for the ColecoVision was the best, "followed surprisingly by the Atari and Intellivision, in that order".[46] Computer and Video Games reviewed the ColecoVision port in its September 1984 issue and scored it 4 out of 4 in all four categories of Action, Graphics, Addiction and Theme.[47]

The Famicom version of the game sold 840,000 units in Japan.[48]

Legal issues[]

In April 1982, Sid Sheinberg, a seasoned lawyer and president of MCA and Universal City Studios, learned of the game's success and suspected it might be a trademark infringement of Universal's own King Kong.[13]:211 On April 27, 1982, he met with Arnold Greenberg of Coleco and threatened to sue over Coleco's home version of Donkey Kong. Coleco agreed on May 3, 1982 to pay royalties to Universal of 3% of their Donkey Kong's net sale price, worth about $4.6 million.[18]:121 Meanwhile, Sheinberg revoked Tiger's license to make its King Kong game, but O. R. Rissman refused to acknowledge Universal's claim to the trademark.[13]:214 When Universal threatened Nintendo, Howard Lincoln and Nintendo refused to cave. In preparation for the court battle ahead, Universal agreed to allow Tiger to continue producing its King Kong game as long as they distinguished it from Donkey Kong.[13]:215

Universal sued Nintendo on June 29, 1982 and announced its license with Coleco. The company sent cease and desist letters to Nintendo's licensees, all of which agreed to pay royalties to Universal except Milton Bradley and Ralston Purina.[49]:74–75 Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo, Co., Ltd. was heard in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by Judge Robert W. Sweet. Over seven days, Universal's counsel, the New York firm Townley & Updike, argued that the names King Kong and Donkey Kong were easily confused and that the plot of the game was an infringement on that of the films.[49]:74 Nintendo's counsel, John Kirby, countered that Universal had themselves argued in a previous case that King Kong's scenario and characters were in the public domain. Judge Sweet ruled in Nintendo's favor, awarding the company Universal's profits from Tiger's game ($56,689.41), damages and attorney's fees.[13]:217

Universal appealed, trying to prove consumer confusion by presenting the results of a telephone survey and examples from print media where people had allegedly assumed a connection between the two Kongs.[50]:118 On October 4, 1984, however, the court upheld the previous verdict.[50]:112

Nintendo and its licensees filed counterclaims against Universal. On May 20, 1985, Judge Sweet awarded Nintendo $1.8 million for legal fees, lost revenues, and other expenses.[13]:218 However, he denied Nintendo's claim of damages from those licensees who had paid royalties to both Nintendo and Universal.[49]:72 Both parties appealed this judgment, but the verdict was upheld on July 15, 1986.[49]:77–78

Nintendo thanked John Kirby with the gift of a $30,000 sailboat named Donkey Kong and "exclusive worldwide rights to use the name for sailboats".[18]:126 A later Nintendo protagonist was named in Kirby's honor.[51] The court battle also taught Nintendo they could compete with larger entertainment industry companies.[18]:127

Legacy[]

In 1996 Next Generation listed the arcade, Atari 7800, and cancelled Coleco Adam versions as number 50 on their "Top 100 Games of All Time", commenting that even ignoring its massive historical significance, Donkey Kong stands as a great game due to its demanding challenges and graphics which manage to elegantly delineate an entire scenario on a single screen.[52] In February 2006, Nintendo Power rated it the 148th best game made on a Nintendo system.[53] Today, Donkey Kong is the fifth most popular arcade game among collectors.[54]

Emulation[]

The NES version was re-released as an unlockable game in Animal Crossing for the GameCube. It was also published on Virtual Console for the Wii, Wii U, and Nintendo 3DS.[55] The Wii U version is also the last game that was released to celebrate the 30-year anniversary of the Japanese version of the NES, the Famicom. The original arcade version of the game appears in the Nintendo 64 game Donkey Kong 64, and must be beaten to finish the game.[56] Nintendo released the NES version on the e-Reader and for the Game Boy Advance Classic NES Series in 2002 and 2004, respectively.[57] In 2004, Namco released an arcade cabinet which contains Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Mario Bros.

Donkey Kong: Original Edition is a port based on the NES version that reinstates the cement factory stage and includes some intermission animations absent from the original NES version, which has only ever been released on the Virtual Console. It was preinstalled on 25th Anniversary PAL region red Wii systems,[58] which were first released in Europe on October 29, 2010.[59] In Japan, a download code for the game for Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console was sent to users who purchased New Super Mario Bros. 2 or Brain Age: Concentration Training from the Nintendo eShop from July 28 to September 2, 2012.[60] In North America, a download code for the game for Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console was sent to users who purchased one of five select 3DS games on the Nintendo eShop and registered it on Club Nintendo from October 1, 2012 to January 6, 2013.[61][62] In Europe and Australia, it was released for purchase on the Nintendo 3DS eShop, being released on September 18, 2014 in Europe[63] and on September 19, 2014 in Australia.[64] The original arcade version was re-released as part of the Arcade Archives series for Nintendo Switch on June 14, 2018,[65] and the NES version was re-released as one of the launch titles for Nintendo Switch Online on September 19, 2018.[66]

Clones[]

Crazy Kong was officially licensed from Nintendo and manufactured by Falcon for some non-US markets. Nevertheless, Crazy Kong machines found their way into some American arcades, often installed in cabinets marked as Congorilla. Nintendo was quick to take legal action against those distributing the game in the US.[50]:119 Bootleg copies of Donkey Kong also appeared in both North America and France under the Crazy Kong, Konkey Kong or Donkey King names. The 1982 Logger arcade game from Century Electronics is a direct clone of Donkey Kong, with a large bird standing in for the ape and rolling logs instead of barrels.[67]

In 1981, O. R. Rissman, president of Tiger Electronics, obtained a license to use the name King Kong from Universal City Studios. Under this title, Tiger created a handheld game with a scenario and gameplay based directly on Nintendo's creation.[13]:210–211

Many home computer clones directly borrowed the gorilla theme: Killer Gorilla (BBC Micro, 1983), Killer Kong (ZX Spectrum, 1983), Crazy Kong 64 (Commodore 64, 1983), Kongo Kong (Commodore 64, 1983), Donkey King (TRS-80 Color Computer, 1983), and Kong (TI-99/4A, 1983). One of the first releases from Electronic Arts was Hard Hat Mack (Apple II, 1983), a three-stage game without an ape, but using the construction site setting from Donkey Kong. Other clones recast the game with different characters, such as Cannonball Blitz (Apple II, 1982), with a soldier and cannonballs replacing the ape and barrels, and the American Southwest-themed Canyon Climber (Atari 8-bit, 1982).[68]

Epyx's Jumpman (Atari 8-bit, 1983) reuses a prototypical name for the Mario character in Donkey Kong. A magazine ad for the game has the tagline "If you liked Donkey Kong, you'll love JUMPMAN!"[69] Jumpman, along with Miner 2049er (Atari 8-bit, 1982) and Mr. Robot and His Robot Factory (Atari 8-bit, 1984), focuses on traversing all of the platforms in the level, or collecting scattered objects, instead of climbing to the top.

There were so many games with multiple ladder and platforms stages by 1983 that Electronic Games described Nintendo's own Popeye game as "yet another variation of a theme that's become all too familiar since the success of Donkey Kong".[70] That year Sega released a Donkey Kong clone called Congo Bongo in arcades.[71] Although using isometric perspective, the structure and gameplay are similar.

Sequels[]

Donkey Kong spawned the sequel Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) with the player controlling Donkey Kong's son in an attempt to save his father from the now-evil Mario. The 1983 spinoff Mario Bros. introduced Mario's brother Luigi in a single-screen cooperative game set in a sewer, and launched the Mario franchise. Also in 1983, Donkey Kong 3 appeared in the form of a fixed shooter, with an exterminator named Stanley ridding the ape—and insects—from a greenhouse.

Later games[]

Nintendo revived the Donkey Kong franchise in the 1990s for a series of platform games and spin-offs developed by Rare, beginning with Donkey Kong Country in 1994. In 2004, Nintendo released Mario vs. Donkey Kong, a sequel to the Game Boy's Donkey Kong, in which Mario must chase Donkey Kong to get back the stolen Mini-Mario toys. In the follow-up Mario vs. Donkey Kong 2: March of the Minis, Donkey Kong once again falls in love with Pauline and kidnaps her, and Mario uses the Mini-Mario toys to help him rescue her. Donkey Kong Racing for the GameCube was in development by Rare, but was canceled when Microsoft purchased the company. In 2004, Nintendo released the first of the Donkey Konga games, a rhythm-based game series that uses a special bongo controller. Donkey Kong Jungle Beat (2005) is a unique platform action game that uses the same bongo controller accessory. In 2007, Donkey Kong Barrel Blast was released for the Nintendo Wii. It was originally developed as a GameCube game and would have used the bongo controller, but it was delayed and released exclusively as a Wii game with no support for the bongo accessory. The Donkey Kong Country series was revived by Retro Studios in 2010 with the release of Donkey Kong Country Returns, and its sequel, Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze, in 2014.

Donkey Kong appears as a game in the Wii U game NES Remix, which features multiple NES games and sometimes "remixes" them by presenting significantly modified versions of the games as challenges. One such challenge features Link from The Legend of Zelda traveling through the first screen to save Pauline. The difficulty is increased compared to the original Donkey Kong because Link cannot jump, as in Zelda.

Super Smash Bros. Brawl includes a demo of the NES version of Donkey Kong, and a stage called "75m", a replica of its Donkey Kong namesake.[72]

In popular culture[]

By late June 1982, Donkey Kong's success had prompted more than 50 parties in the U.S. and Japan to license the game's characters.[13]:215 Mario and his simian nemesis appeared on cereal boxes, board games, pajamas, and manga. In 1983, the animation studio Ruby-Spears produced a Donkey Kong cartoon (as well as Donkey Kong Jr.) for the Saturday Supercade program on CBS. In the show, mystery crime-solving plots in the mode of Scooby-Doo are framed around the premise of Mario and Pauline chasing Donkey Kong (voiced by Soupy Sales), who has escaped from the circus. The show lasted two seasons.

In 1982, Buckner & Garcia and R. Cade and the Video Victims both recorded songs ("Do the Donkey Kong" and "Donkey Kong", respectively) based on the game. Artists like DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince and Trace Adkins referenced the game in songs. Episodes of The Simpsons, Futurama, Crank Yankers and The Fairly OddParents have referenced the game. Even today, sound effects from the Atari 2600 version often serve as generic video game sounds in films and television series. The phrase "It's on like Donkey Kong" has been used in various works of popular culture. In November 2010, Nintendo applied for a trademark on the phrase with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.[73]

Competition[]

Hank Chien at the Kong Off 3 tournament in Denver, Colorado

The 2007 documentary The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters tells the story of Steve Wiebe's attempts to break the Donkey Kong world record, then considered to have been held by Billy Mitchell.[74] In the early 2010s, Hank Chien set a record of 1,138,600. This was broken four years later by Robbie Lakeman.[75] The current world record was set by John McCurdy on May 25, 2019, with a score of 1,259,000.[76]

In 2018, Mitchell was stripped of his records by Twin Galaxies and banned from submitting new scores after Twin Galaxies concluded that Mitchell had illicitly used emulators to achieve his scores.[77] Twin Galaxies prohibits the use of emulators for high scores they publish because they allow undetectable cheating.[77] However, in 2020 Guinness World Records reversed their decision and reinstated Billy Mitchell's previous world records, based on new evidence including eyewitness reports and expert testimonials.[78]

Notes[]

- ↑ The Family Computer/Nintendo Entertainment System version was ported by Nintendo Research & Development 2.

- ↑ Japanese: ドンキーコング Hepburn: Donkī Kongu

- ↑ "And we received from Coleco an agreement that they would pay us three percent of the net sales price [of all the Donkey Kong cartridges Coleco sold]." It turned out to be 6 million cartridges, which translated into $4.6 million.[18]:121

References[]

- ↑ McFerran, Damien (2018-02-26). "Feature: Shining A Light On Ikegami Tsushinki, The Company That Developed Donkey Kong". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 2020-09-10.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Retro Diary". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing) (104): 13. July 2012. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ↑ Crawford, Chris (2003). Chris Crawford on Game Design. New Riders Publishing.

- ↑ Space Panic at AllGame

- ↑ "The Player's Guide to Climbing Games". Electronic Games 1 (11): 49. January 1983. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160319134356/https://archive.org/stream/Electronic_Games_Volume_01_Number_11_1983-01_Reese_Communications_US.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar. October 8, 2010. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sellers, John (2001). Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to the Golden Age of Video Games. Philadelphia: Running Book Publishers.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 De Maria, Rusel, and Wilson, Johnny L. (2004). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Osborne.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Seth Gordon (director) (2007). The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (DVD). Picturehouse.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Rus (September 14, 2010). "IGN Presents The History of Super Mario Bros". IGN. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ray, Sheri Graner (2004). Gender Inclusive Game Design: Expanding the Market. Hingham, Massachusetts: Charles Rivers Media, Inc.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 Kohler, Chris (2005). Power-up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. Indianapolis, Indiana: BradyGAMES.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 Kent, Steven L. (2002). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Random House International. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7. OCLC 59416169. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160624183529/https://books.google.com/books?id=PTrcTeAqeaEC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Copyright law decisions. Commerce Clearing House. 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=WVdsAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved February 26, 2012. "An English translation of the Japanese term Donkey Kong is "crazy gorilla." Nintendo Co., Ltd. expended over $100,000.00 in direct development of the game, and Nintendo Co., Ltd. hired Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. to provide mechanical programming assistance to fix the software created by Nintendo Co., Ltd. in the storage component of the game. The name "Ikegami Co. Lim." appears in the computer program for the Donkey Kong game. Individuals within the research and development department of Nintendo Co., Ltd., however, created the Donkey Kong concept and game."

- ↑ Company:Ikegami Tsushinki Archived January 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Game Developer Research Institute. Retrieved on May 17, 2009.

- ↑ It started from Pong (それは『ポン』から始まった : アーケードTVゲームの成り立ち, sore wa pon kara hajimatta: ākēdo terebi gēmu no naritachi), Masumi Akagi (赤木真澄, Akagi Masumi), Amusement Tsūshinsha (アミューズメント通信社, Amyūzumento Tsūshinsha), 2005, ISBN 4-9902512-0-2.[page needed]

- ↑ East, Tom (November 25, 2009). "Donkey Kong Was Originally A Popeye Game". Official Nintendo Magazine. Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

Miyamoto says Nintendo's main monkey might not have existed.

<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles> - ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 18.13 18.14 18.15 Sheff, David (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue: The Maturing of Mario. Wilton, Connecticut: GamePress.

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara; Mikkelson, David (February 25, 2001). "Donkey Wrong". Snopes. Retrieved August 29, 2014.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Miyamoto Shrine: Shigeru Miyamoto's Home on The Web". Interview with Miyamoto (May 16, 2001, E3 Expo). Archived from the original on July 2, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2007.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Famicom 20th Anniversary Original Sound Tracks Vol. 1 (Media notes). Scitron Digital Contents Inc. 2004. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Donkey Kong". Smash Bros. DOJO!!. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2008.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Making the Famicom a Reality, Nikkei Electronics (September 12, 1994) (translation by Nathan Altice)

- ↑ Nathan Altice (2015), I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform, page 55 Archived February 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, MIT Press

- ↑ Nathan Altice (2015), I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform, page 362 Archived February 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, MIT Press

- ↑ Nathan Altice (2015), I Am Error: The Nintendo Family Computer / Entertainment System Platform, page 69 Archived February 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, MIT Press

- ↑ Donkey Kong commercial. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170209123741/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ePUeCFOMTM. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ↑ Donkey Kong Junior commercial. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170209122223/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Lv6Rh2Ha40. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Coleco Rolls Videogame Line". Arcade Expres 1 (2): 3. August 30, 1982. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160926002449/https://archive.org/details/arcade_express_v1n2.

- ↑ Harmetz, Aljean (January 15, 1983). "New Faces, More Profits For Video Games". Times-Union: p. 18. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=jnhcAAAAIBAJ&sjid=a1cNAAAAIBAJ&pg=4201,2482231. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ↑ "More Mini-Arcades A Comin'". Electronic Games 4 (16): 10. June 1983. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130122041852/http://www.archive.org/stream/electronic-games-magazine-1983-06/Electronic_Games_Issue_16_Vol_02_04_1983_Jun. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Coleco Mini-arcades G Gold". Arcade Express 1 (1): 4. August 15, 1982. https://archive.org/details/arcade_express_v1n1.

- ↑ Marley, Scott (December 2016). "SG-1000". Retro Gamer (Future Publishing) (163): 56–61.

- ↑ Iwata, Satoru. "Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros: Volume 2: It All Began In 1984". iwataasks.nintendo.com. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

I worked on a wide variety of titles together with R&D2, including Donkey Kong5, which was released at the same time as the Famicom

<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles> - ↑ "Donkey Kong Easter Egg Discovered 26 Years Later". Kotaku.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2013.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Donkey Kong and Me". Dadhacker.com. March 4, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2013.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Hodges, Don (July 1, 2009). "Donkey Kong Lays an Easter Egg". Archived from the original on September 6, 2011.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Weiss, Brett Alan. "Donkey Kong – Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2017.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Jörg Ziesak (2009), Wii Innovate – How Nintendo Created a New Market Through Strategic Innovation, GRIN Verlag, p. 2029, ISBN 978-3-640-49774-4, archived from the original on April 18, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160418041705/https://books.google.com/books?id=C8rHXoUCbfAC&pg=PA2029, retrieved April 9, 2011, "Donkey Kong was Nintendo's first international smash hit and the main reason behind the company's breakthrough in the Northern American market. In the first year of its publication, it earned Nintendo 180 million US dollars, continuing with a return of 100 million dollars in the second year."

- ↑ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25 - テーブル型TVゲーム機 (Table Videos)". Game Machine (Amusement Press, Inc.) (221): 29. 1 October 1983.

- ↑ Pearl, Rick (June 1983). "Closet Classics". Electronic Games: p. 82. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150107032556/http://www.archive.org/stream/electronic-games-magazine-1983-06/Electronic_Games_Issue_16_Vol_02_04_1983_Jun. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Electronic Games Magazine". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2012.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Edwards, Richard A. (January 1983). "Capsule Reviews". The Space Gamer (Steve Jackson Games) (59): 44, 46.

- ↑ "Arcade Express" (PDF). Reese Publishing Co. September 26, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Linzmayer, Owen (Spring 1983). "Home Video Games: Colecovision: Alive With Five". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games: 50. http://www.atarimagazines.com/cva/v1n1/colecovision.php.

- ↑ Goodman, Danny (Spring 1983). "Home Video Games: Video Games Update". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games: 32. http://www.atarimagazines.com/cva/v1n1/vgupdate.php.

- ↑ "File:CVG UK 035.pdf". Retro CDN. August 31, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Japan Sales". Nintendojo. September 26, 2006. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles> (Translation)

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo, Co., Ltd., United States Second Circuit Court of Appeals, July 15, 1986

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo, Co., Ltd., United States Second Circuit Court of Appeals, October 4, 1984

- ↑ "How did Mario get his name... and the origins of your favourite Nintendo stars – Official Nintendo Magazine". September 24, 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2017.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (21): 52. September 1996.

- ↑ Michaud, Pete (February 2006). "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power 197: 58.

- ↑ McLemore, Greg, et al. (2005). "The Top Coin-operated Videogames of All Time Archived January 27, 2013, at WebCite". Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (October 31, 2006). "Wii Virtual Console Lineup Unveiled". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2006.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Casamassina, Matt (November 24, 1999). "Donkey Kong 64 review". IGN. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2019.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "ファミコンミニ/ドンキーコング". Nintendo. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kemps, Heidi (November 16, 2010). "Europe gets exclusive 'perfect version' of NES Donkey Kong in its Mario 25th Anniversary Wiis". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Axon, Samuel (October 12, 2010). "Nintendo Announces 25th Anniversary Mario Consoles for Europe". Mashable. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Gantayat, Anoop (July 20, 2012). "Nintendo Kicks off Download Game Sales With Campaign". Andriasang. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Donkey Kong Free Game Giveaway". Club Nintendo. Nintendo. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Schreier, Jason (October 1, 2012). "Buy One Of Five 3DS Games Online And You Get A Free Copy Of Donkey Kong: Original Edition". Kotaku. Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Warmuth, Christopher. "Europe: Original Donkey Kong Edition & Japan: Mario Pinball Land". Mario Party Legacy. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Vuckovic, Daniel (September 18, 2014). "Nintendo Download Updates (19/9) Beats, Rhythm and Warriors". Vooks. Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (June 14, 2018). "Two Long-Lost Nintendo Arcade Games Are Heading To Switch". Kotaku. Retrieved June 21, 2018.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Good, Owen S. (September 13, 2018). "Nintendo Switch Online has these 20 classic NES games". Polygon. Retrieved April 5, 2019.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Logger". Killer List of Video Games. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Canyon Climber. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnJU4fiiE2w.

- ↑ "Epyx Jumpman ad". Electronic Games Magazine: 81. June 1983.

- ↑ Sharpe, Roger C. (June 1983). "Insert Coin Here". Electronic Games: p. 92. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150107032556/http://www.archive.org/stream/electronic-games-magazine-1983-06/Electronic_Games_Issue_16_Vol_02_04_1983_Jun. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Congo Bongo". Arcade History.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Smash Bros. DOJO!! – 75m". Smash Bros.Dojo. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2008.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Gross, Doug (November 10, 2010). "Nintendo seeks to trademark 'On like Donkey Kong'". CNN. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121022200616/http://edition.cnn.com/2010/TECH/gaming.gadgets/11/10/on.like.donkey.kong/index.html. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ↑ "The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters > Overview". Allmovie. Archived from the original on July 22, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Good, Owen S. (September 6, 2014). "Newcomer sets all-time high score in Donkey Kong". Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "Arcade - Donkey Kong - Points [Hammer Allowed] - 1,259,000 - John McCurdy". Twin Galaxies. Retrieved February 10, 2020.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Crecente, Brian. "'King of Kong' Star Stripped of High Scores, Banned From Competition". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved November 25, 2018.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ "A statement from Guinness World Records: Billy Mitchell". Guinness World Records. June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

<templatestyles src="Div col/styles.css"/>

- Consalvo, Mia (2003). "Hot Dates and Fairy-tale Romances". The Video Game Theory Reader. New York: Routledge.

- Fox, Matt (2006). The Video Games Guide. Boxtree Ltd.

- Mingo, Jack. (1994) How the Cadillac Got its Fins New York: HarperBusiness. ISBN 0-88730-677-2

- Schodt, Frederick L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press.

External links[]

- Donkey Kong at the Killer List of Videogames

- Donkey Kong at Arcade History

| Donkey Kong high score competition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Notable players | Hank Chien • Billy Mitchell • Robbie Lakeman • Steve Wiebe | |

| Related articles | The King of Kong • Twin Galaxies • Walter Day | |